content combined w/ research page

The benefits of taking a gap year are many and blend together across multiple areas. We have attempted to cut to the chase by sifting and sorting the benefits into statistically proven benefits and some of the less tangible benefits that more play a role in shaping the person. Taking a structured gap year invariably serves to develop the individual into a more focused student with a better sense of purpose and engagement in the world.

From Joe O’Shea’s book, Gap Year: How Delaying College Changes People in Ways the World Needs:

“Some studies have looked at the academic performance of gap year students while in college. In Australia and the United Kingdom, economic researchers found that high school students who deferred their admission to college to take a Gap Year went to college (after their gap year) at the same rate as those who accepted an offer and intended to go straight there (Birch and Miller 2007; Crawford and Cribb 2012). They also found that taking a gap year had a significant positive impact on students’ academic performance in college, with the strongest impact for students who had applied to college with grades on the lower end of the distribution (Birch and Miller 2007; Crawford and Cribb 2012).”

In fact, in the United Kingdom and in the United States, students who had taken a Gap Year were more likely to graduate with higher grade point averages than observationally identical individuals who went straight to college, and this effect was seen even for gap year students with lower academic achievement in high school (Crawford and Cribb 2012, Clagett 2013).

2020 National Alumni Survey

Following the highly successful 2015 National Alumni Survey, the Gap Year Association commissioned the efforts of Kempie Blythe, MA, and reprising her role from the 2015 survey, Nina Hoe Gallagher, PhD, as well as the GYA Research Committee, to complete the 2020 Gap Year Alumni Survey. The previous survey has been cited by scholars, media, and providers demonstrating strong returns for gap year participants and this data more than confirms the great results we see through almost every gap year graduate.

In total, 1,795 respondents began the Gap Year Alumni 2020 Survey, and of those, 1, 596 participated in a “gap year” that aligned with the definition in the survey and 1,139 were eligible as permanent residents or citizens of the U.S. or Canada. A total of 1,190 gap year alumni completed this survey. The Alumni Outcomes Summary Report 2015 collected stratified data from a total of 498 NCCC alumni from 2004, 2009, and 2012 (respectively 10, 5, and 2 years after the end of service).

Annual State of the Field Survey - 2019/2020

Each year the GYA Research Committee authors a survey tool to track year-over-year trends for gap year participation and outcomes as a short-term snapshot. In 2019/20 we had reporting from almost 50 organizations and expect that to grow each year. The tool answers questions about enrollment, demographics, marketing, and early outcomes. The Research Committee takes the completed data and shares two reports, one comprehensive (reserved only for survey participants), and one general version that is available to the public. Click here for the 2019 survey.

Surveys will be launched in the spring of each year, and finalized in the summer of that same year. We have two separate survey results as the committee continues to reach new heights of quality: Gap Year Programs, and Gap Year Counselors.

Download for program providers and counselors, respectively:

Current Data About Gap Years

- 90 percent of students who took a gap year returned to college within a year.http://online.wsj.com

- In 2016 Gap Year Association Members and Provisional Members gave away a combined total of more than $4,200,000 in scholarships and needs-based grants. [2016 GYA survey]

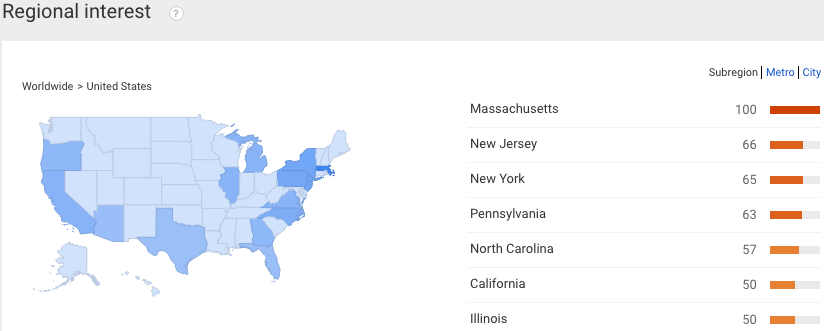

- Gap year interest and enrollment trends continue to grow. We don’t know exactly how many US students take a gap year each year, but amongst our sources we are able to say that interest and enrollment is growing substantively.

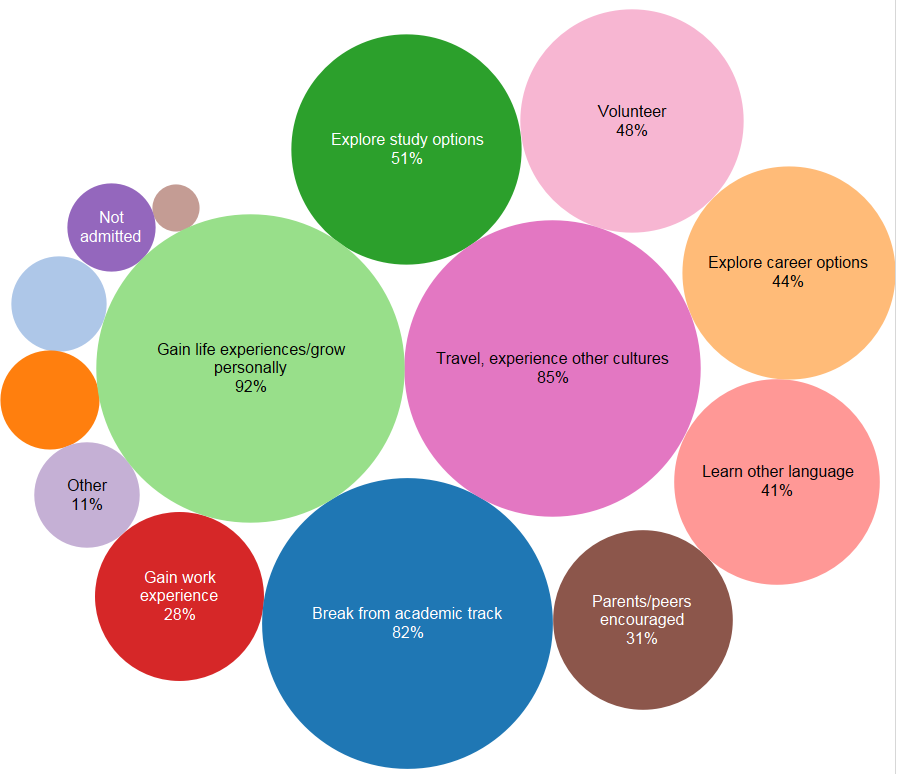

The following chart, a part of the 2015 National Alumni Survey which was undertaken by Nina Hoe, PhD, in collaboration with the Institute for Survey Research, Temple University, and the GYA Research Committee, details what our respondents cited as their most significant influences when deciding to take a gap year.

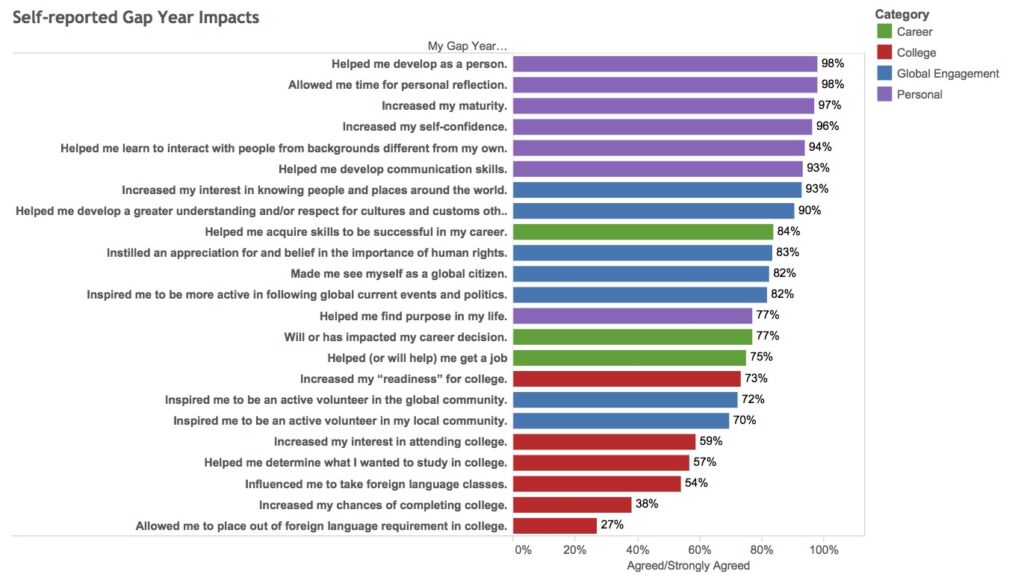

The following chart details the most significant experiences respondents had while on their gap year. (… note that partying is extremely underrepresented).

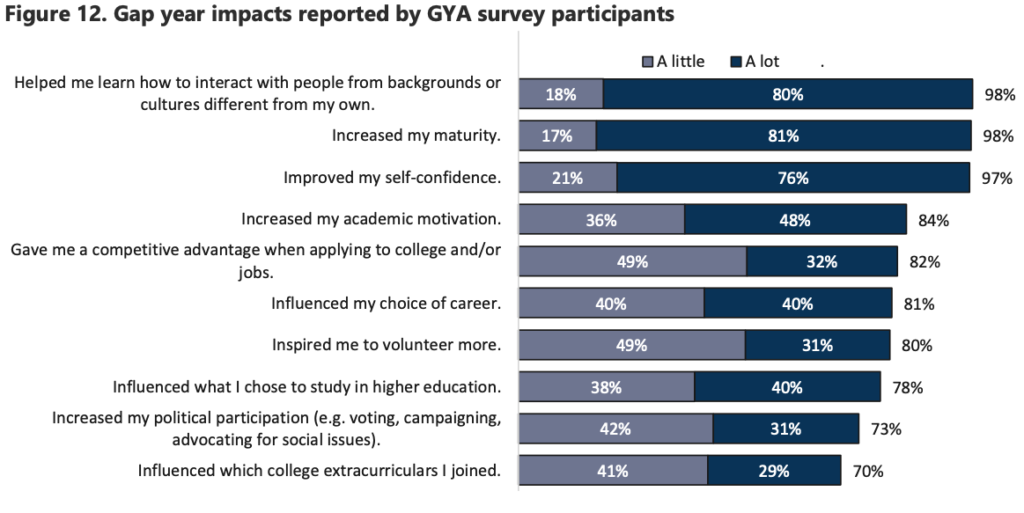

The following chart details the most significant outcomes reported while on their gap year, broken down by color based on Personal, Global Engagement, Career & College.

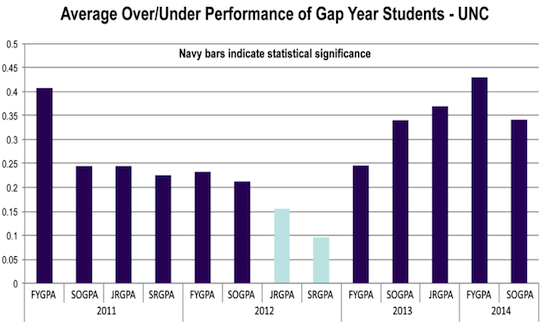

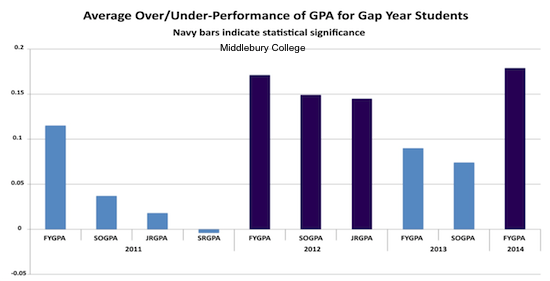

A recent methodology to track gap year students’ over/underperformance of GPA was designed by Bob Clagett, former Dean of Admissions at Middlebury College. This methodology tracked the academic rating of an incoming student including everything of an academic nature that is received in the application process (grades, rigor of high school program, scores, teacher and counselor recommendations, even “fire in the belly” as demonstrated in the applicant’s essays). It is usually an excellent predictor for academic performance in college. When Clagett controlled for the academic rating and looked at the actual academic performance of students who took a Gap Year compared to their predicted performance based on their academic rating, students who took a gap year almost always overperformed academically in college, usually to a statistically significant degree. Most importantly, the positive effect of taking a gap year was demonstrated to endure over all four years.

- Students who have taken a gap year overwhelmingly report being satisfied with their jobs. Upon further inquiry, Haigler found that this was related to a less-selfish approach to working with people and careers. [Karl Haigler & Rae Nelson, The Gap Year Advantage, independent study of 280 Gap Year students between 1997 – 2006]

- The highest three rated outcomes of gap years is that of gaining “a better sense of who I am as a person and what is important to me” followed by “[the gap year] gave me a better understanding of other countries, people, cultures, and ways of living” and “[it] provided me with additional skills and knowledge that contributed to my career or academic major.” [Haigler & Nelson, independent study of 280 Gap Year students]

- Burnout from the competitive pressure of high school and a desire “to find out more about themselves,” are the top two reasons students take gap years, according to a survey of 280 people who did so by Karl Haigler and Rae Nelson of Advance, N.C., co-authors of a forthcoming guidebook on the topic. [http://online.wsj.com]

- For most students, gap year experiences have an impact on their choice of academic major and career – either setting them on a different path than before a gap year or confirming their direction (60% said the experience either “set me on my current career path/academic major” or “confirmed my choice of career/academic major”). [Karl Haigler & Rae Nelson, The Gap Year Advantage, independent study of 300 gap year students between 1997 – 2006]

- National statistics show that half of medical school-minded students are taking at least one gap year, he says. The percentage is even higher – 60% – for undergrads at high-powered research institutions such as Johns Hopkins heading for medical schools nationwide. [The Journal Science]

- A new study of more than 900 first-year students by Sydney University researchers has revealed that not only did taking a year off have a positive effect on students’ motivation, it also translated to a real boost in performance in the first semesters at university. [http://www.heraldsun.com.au]

- Many teenagers in other countries wait a year after high school before heading to college. In Norway, Denmark and Turkey, for instance, more than 50 percent of students take a year off before college, according to the Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education in Oslo, Norway.” [ http://www.desmoinesregister.com]

- In 2010, young adults ages 25–34 with a bachelor’s degree earned 114 percent more than young adults without a high school diploma or its equivalent, 50 percent more than young adult high school completers, and 22 percent more than young adults with an associate’s degree. [http://nces.ed.gov]

- About one-third of college freshmen don’t return to the same institution for a second year, according to ACT Inc., an education testing company in Iowa City. [http://www.desmoinesregister.com]

- As recently as the mid-1990’s, the American college-graduation rate was the highest in the world. However, in the past decade or so, the United States has fallen from first to twelfth in the percentage of its twenty-five to thirty-four year-olds with Bachelors degrees. [Paris: OECD Centre for Educational Research and Innovation Publishing, 2011, pg 40. http://www.cnesus.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/deata/cps/historical/index.html]

- “College graduates ages 25 to 32 who were working full time now typically earn about $17,500 more annually than employed young adults with just a high school diploma ($45,500 vs. $28,000); those with a two-year degree or some college training earned $30,000. [Salt Lake Tribune].

- “Median earnings for high-school graduates have fallen more than $3,000, from $31,384 in 1965 to $28,000 last year. Young adults with just high-school diplomas now are also much more likely to live in poverty, at 22 percent compared to 7 percent for their counterparts in 1979. [Salt Lake Tribune]

- In 1961 the average full-time college student spent 24 hours per week studying outside of the classroom. By 1981 that number had dropped to 20 hours, and in 2003 the average student spent only 14 hours per week studying outside of the classroom. [Phillip Babcock and Mindy Marks, “Leisure College, USA: The Decline in Student Study Time,” AEI Education Outlook, August 2010]. A separate study at the University of California found that students spend fewer than 13 hours per week studying, and 12 hours hanging out with friends, 14 hours consuming entertainment, and 11 hours using computers for fun, and 6 hours exercising. [Steven Brint and Allison M. Cantwell, “Undergraduate Time Use and Academic Outcomes: Results from UCUES 2006]

- Gap year students are perceived to be ‘more mature, more self-reliant and independent’ than non-gap year students. [Birch, “The Characteristics of Gap-Year Students and Their Tertiary Academic Outcomes”, Australia, 2007]

- Taking a 1-year break between high school and university allows ‘motivation for and interest in study to be renewed.’ [Birch, “The Characteristics of Gap-Year Students and Their Tertiary Academic Outcomes”, Australia, 2007]

- 88 percent of gap year graduates report that their gap year had significantly added to their employability. [Milkround graduate recruitment Gap Year survey, http://www.milkroundonline.com]

- Australian students were more likely to take a gap year if they had low academic performance and motivation in high school. Yet former “gappers” reported significantly higher motivation in college – in the form of “adaptive behavior” such as planning, task management, and persistence – than did students who did not take a gap year. Furthermore, “gappers” reported a lessened instance of “mal-adaptive” behavior” as a result of their gap year. [Martin, Andrew J., Journal of Educational Psychology, “Enhancing student motivation and engagement: The effects of a multidimensional intervention,” 2008]